Convergence Fellowship Program

Funding Government in the Age of AI

By

Ky-Cuong Huynh, Suchet Mittal, Noah Frank

August 21, 2025

This paper explores nine public revenue strategies that support preserving governmental fiscal stability in an increasingly automated economy, even if traditional labor income-based taxation declines.

Authors

Key Advisors

Originally Published

August 21, 2025

Research program

AI Economic Policy Fellowship: Spring 2025

This project was conducted as part of SPAR Spring 2025, a research fellowship connecting rising talent with experts in AI safety or policy.

Abstract

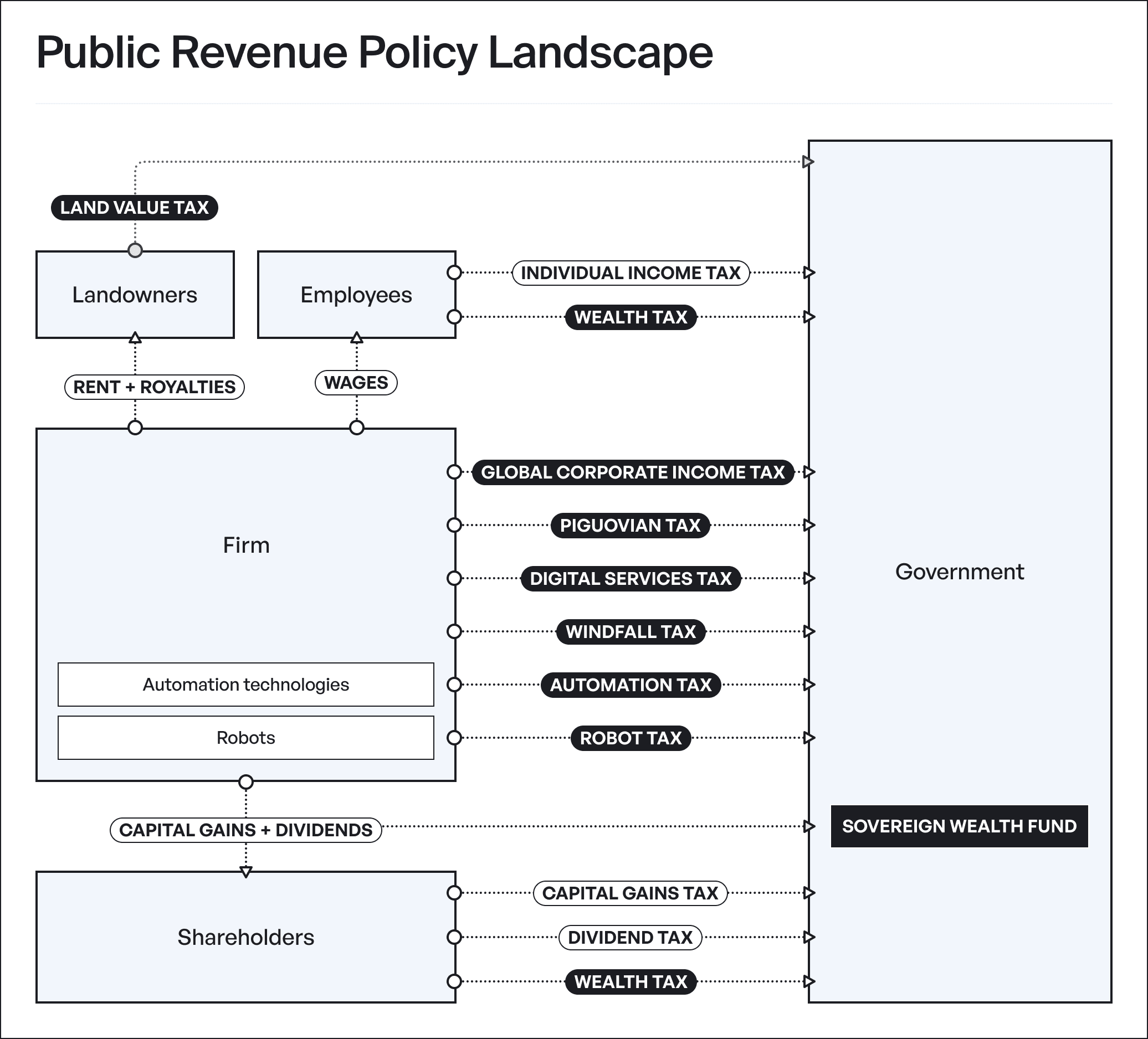

Transformative artificial intelligence (TAI) will reshape how economies generate and allocate value. It poses three fundamental challenges to public finance: widespread labor displacement that erodes wage-based tax revenues, borderless economic activity that defies geographically rooted levies, and concentration of economic gains that bypasses existing taxation mechanisms. A new approach to funding government is needed. Our work assesses the performance of nine public revenue strategies across scenarios that vary in their levels of labor displacement, productivity growth, and gains concentration. To do so, we build upon traditional tax evaluation approaches and introduce the FIRI Framework (Feasibility, Incidence, Resilience, and Incentives) to handle TAI-specific concerns. We identify the most promising portfolio of policy options, pinpoint key trade-offs, and highlight where future research should focus.

Executive Summary

Transformative AI (TAI) is coming. How will governments remain funded as TAI systems, capable of driving societal transformation on par with the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions, reshape economic activity? Fiscal policy will need to adapt to the possibility of widespread labor displacement, the ongoing digitalisation of economic activity, and the poor fit of existing tax systems for steering and sharing AI-driven prosperity.

Policymakers will also need to contend with the lack of expert consensus on the specific trajectory of transformative AI. To handle the wide range of plausible futures, we take a scenario planning approach (Katze 2024), with labor demand, productivity gains, and gains concentration as our strategic variables. From these, we produce eight possible futures by defining high/low variations of each variable, examining their combinations, and selecting five as in-scope for our work.

In evaluating policy options under our scenarios, we found existing tax frameworks do not hold up under possible TAI futures. To understand these issues, we build upon existing expert consensus to introduce the FIRI Framework: Feasibility (implementation difficulty), Incidence (economic burden distribution), Resilience (durability over time), and Incentives (behavioral effects). The results favor a hybrid strategy of multiple approaches over any single revenue instrument.

Key Findings

1

Current systems are structurally vulnerable. Labor income and social insurance taxes comprise 50.4% of public revenue in OECD countries (Bunn 2022). TAI threatens to simultaneously reduce this revenue base through labor displacement while increasing spending needs for displaced worker support. Fiscal capacity would contract just as governments face unprecedented demands to fund new social safety nets.

2

Two policy instruments perform especially well.

Land Value Taxes have desirable incidence (the owners of the most valuable land pay the most) and incentive alignment (land must be used productively) properties. Land remains scarce, observable, and a key driver of productivity, even under TAI conditions. A land value tax would be most feasible if implemented at the local level, where the information and infrastructure for property taxes already exist.

Consumption Taxes are already widely employed, have less volatility under economic downturns, and are minimally distortive when implemented as a value-added tax. They remain reliable even as employment contracts and can be paired with redistribution to offset regressivity.

3

Complementary tools address distinct gaps.

A Global Corporate Income Tax would be a technically feasible way to target mobile economic rents, but relies on sustained international coordination.

Sovereign Wealth Funds and Windfall Clauses offer mechanisms to capture and redeploy AI-generated wealth but depend on strong governance and forward-looking design.

Net Wealth Taxes face valuation and compliance risks but can directly target capital concentration in inequality-driven futures.

4

Lower-scoring instruments have flawed fundamentals.

Automation Taxes suffer from challenges with defining what qualifies as undesirable automation and making that observable and measurable for enforcement.

Digital Services Taxes are actively being replaced under current OECD plans. In addition to multiplying compliance overhead for firms, they produce adversarial dynamics between countries that are counterproductive to global cooperation. Even as an interim solution, they make an ultimate solution harder to reach.

Pigouvian Taxes are appealing in principle for changing incentives by pricing harms (i.e., internalizing externalities). Their feasibility is low due to the difficulty of building consensus around which externalities are harmful, measuring them, and attributing them to specific actors.

Note that we considered many reforms of taxes on individuals to be out-of-scope for this paper. See the Appendix for details.

Policy Implications

If transformative AI emerges as anticipated, no single revenue policy can address the resulting fiscal challenges. We recommend that policymakers:

Prepare for multiple futures while acting on current trends. If AI capabilities continue scaling rapidly, the window for proactive intervention narrows as economic power concentrates. Waiting would make reform more difficult and less effective. Scenario-specific policy responses should be prepared in advance, with consideration for higher-order effects (Sampanthar, Frank, and Balakrishnan 2025).

Prioritize TAI-specific research on resilient revenue instruments. Consumption taxes and land value taxes appear most promising if economies are significantly reshaped by automation. Even an increasingly automated economy would still have taxable purchases of goods and services, while land value taxes can tap into wealth reinvested from many sources. However, both strategies require substantial TAI-specific modeling and policy analysis before they are implementation-ready.

Enhance government AI expertise. States need technical capacity to effectively understand, monitor, and regulate AI-driven economic activity. Recruiting and retaining technical talent in government should be seen as a matter of national importance.

Coordinate implementation across government levels and respect subsidiarity. Different revenue instruments naturally fit different governmental levels based on administrative capacity and information availability. Land value taxes align well with local government infrastructure (building on existing property tax systems), while global corporate income taxes require supranational coordination. Consumption taxes can be implemented at multiple levels but benefit from harmonized rates to prevent distortions. Unilateral approaches add compliance burden, risk double taxation, and produce adversarial dynamics between all actors involved. The principle of subsidiarity, where taxation is handled at the lowest level of government with the requisite information and infrastructure, should be the guiding approach, with higher-level coordination as-needed (Keen and de Mooij 2008; Vischer 2001).

Improve economic observability. Governments should avoid being surprised by AI diffusion that may rapidly accelerate. To this end, new macroeconomic indicators should be identified and adopted. For example, monetary policy today balances unemployment and inflation as concerns. Central bankers thus monitor measures of both closely. In a world where most work is automated, quantifying capital utilization (compute capacity, the number of active robots and drones, etc.) would become more important (Korinek 2024). Other plausibly useful indicators include the time horizon and complexity of tasks being automated, automation-driven unemployment, and concentration measures for both market power and wealth distribution.

Accelerate international coordination. Unilateral governance approaches exacerbate compliance burdens, jurisdictional arbitrage, and trade conflicts, as seen today with digital commerce. These challenges will only be amplified in a multipolar world of multiple great powers with access to transformative AI. Governments should strengthen multilateral frameworks now, building on progress from OECD BEPS 2.0 while preparing AI-specific modifications.

Ultimately, the foundations of democratic governance are at stake. Governments that diversify their revenue sources, build technical expertise, and strengthen international cooperation will be best positioned to guide their citizens through the coming socioeconomic transformation.

Structure of This Paper

In Section I, we explain why current tax systems are poorly suited to economies reshaped by transformative AI. Section II introduces a scenario framework built around three key variables: labor demand, productivity gains, and gains allocation.

Section III presents the FIRI Framework to assess tax instruments built atop existing work like the Ottawa Taxation Framework Conditions. Section IV applies FIRI across nine revenue strategies, identifying trade-offs and critiquing performance.

Section V integrates these findings into a portfolio approach. Lastly, Section VI outlines outstanding research needs and Section VII offers parting thoughts.

Get research updates from Convergence

Leave us your contact info and we’ll share our latest research, partnerships, and projects as they're released.

You may opt out at any time. View our Privacy Policy.